From Tangible to Intangible: The Evolution of Global E-commerce in the Digital Age

Ecommerce: The Difference between Physical and Digital Goods

As the digital economy continues to grow, so do non-tangible products. Often, when discussing ecommerce online, the focus is solely on selling physical goods. However, it is important to distinguish between the two domains of selling physical products and digital products or services because they have entirely different business models. Physical products require inventory and storage, as well as relying on certain logistics. Platforms like Shopify have built a whole ecosystem to support small business owners in selling their products, while Etsy offers a platform for selling artisanal products from the comfort of one's own home. Physical products also face geographical challenges when sold internationally; the recent example of Brexit causing complicated customs regulations has significantly impacted many small online retailers' businesses. I have written more about this issue here.

Selling digital products and services has become much easier online. In the past, during the early 2000s, not many people would have been willing to pay for online courses, excel templates, or ebooks because payment systems were not available and these types of digital products were not widely offered. However, over the last decade, there has been a significant shift in this trend as online courses and templates for various services (such as Notion) have emerged as potential sources of revenue.

The Growth in Digital Trade

Products and services like these pique my interest, as they have the potential to be developed and sold globally. However, for those living in developing countries, obtaining a payment gateway that is accepted can be quite challenging. Even Stripe, one of the largest online payment-processing services, is only available in 46 countries.

However, the digital economy is filled with a wide variety of niche products and services that continue to gain traction, although there is limited data available. This mirrors the issue discussed in my recent article on the global freelance economy. A noteworthy perspective can be found in Stripe's report "How Digital Trade is Reshaping the Global Economy" set for release in 2023, which focuses on small and micro businesses but only includes a select group of countries.

- 59% of consumers are open or somewhat open to purchase a digital service from abroad in 2023

- 88% of education businesses sell internationally today, and 70% plan to expand further internationally in the next two years.

- 81% of sole proprietor businesses in our survey now sell to more than one market, heralding the rise of single-person multinationals. Eighteen percent of these sell to more than 11 global markets.

According to Stripe these are the top 10 digital exports categories by cross-border payment in 2022

- Software (fully digital)

- Clothing and accessoires

- Travel and lodging

- Business services (potentially fully digital)

- Merchandise

- Education (potentially fully digital)

- Ticket and events

- Speciality retail

- Digital goods (digital)

- Person services (potentially fully digital)

Half of the categories can be considered completely digital in nature, consisting of various online products and services. These digital trade routes are seeing immense growth between countries according to data from Stripe. For example, there is a new trade route emerging with a growth rate of 89% between France and Germany from 2020 to 2021, and a staggering 150% growth rate between Japan and Taiwan.

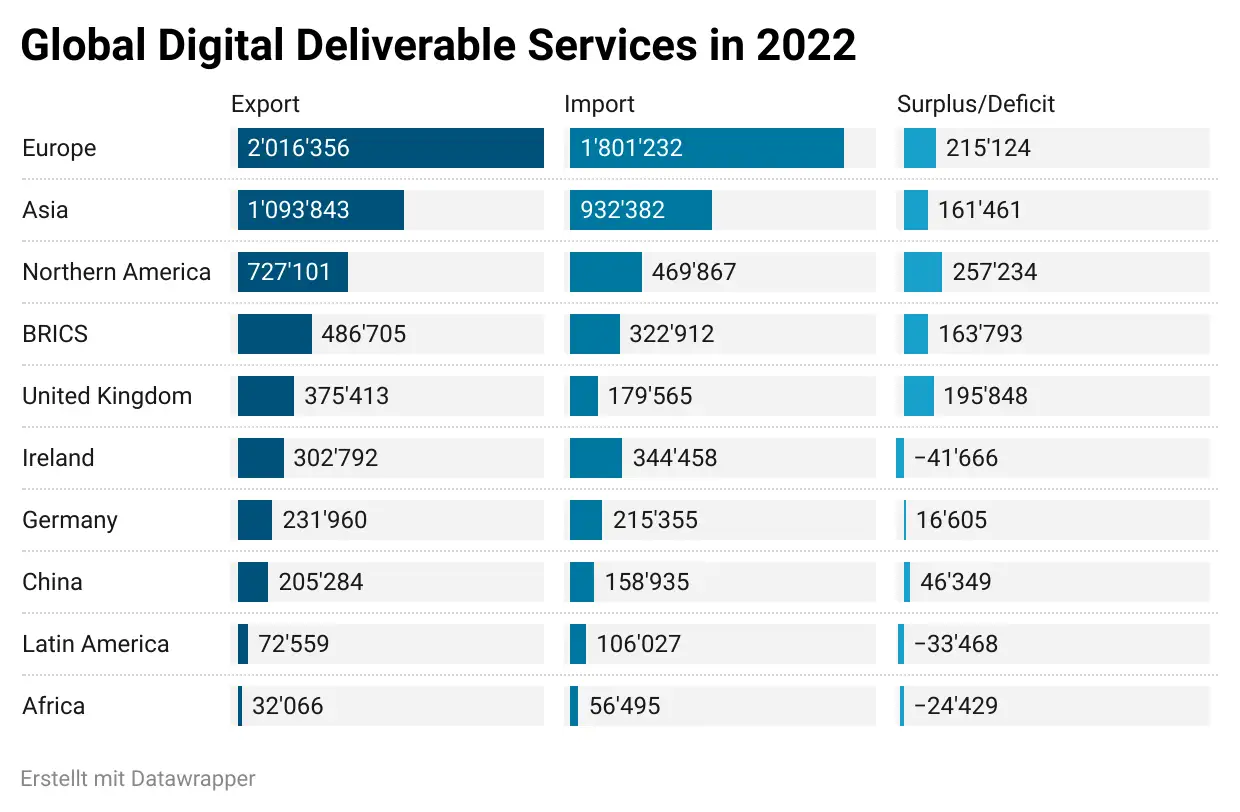

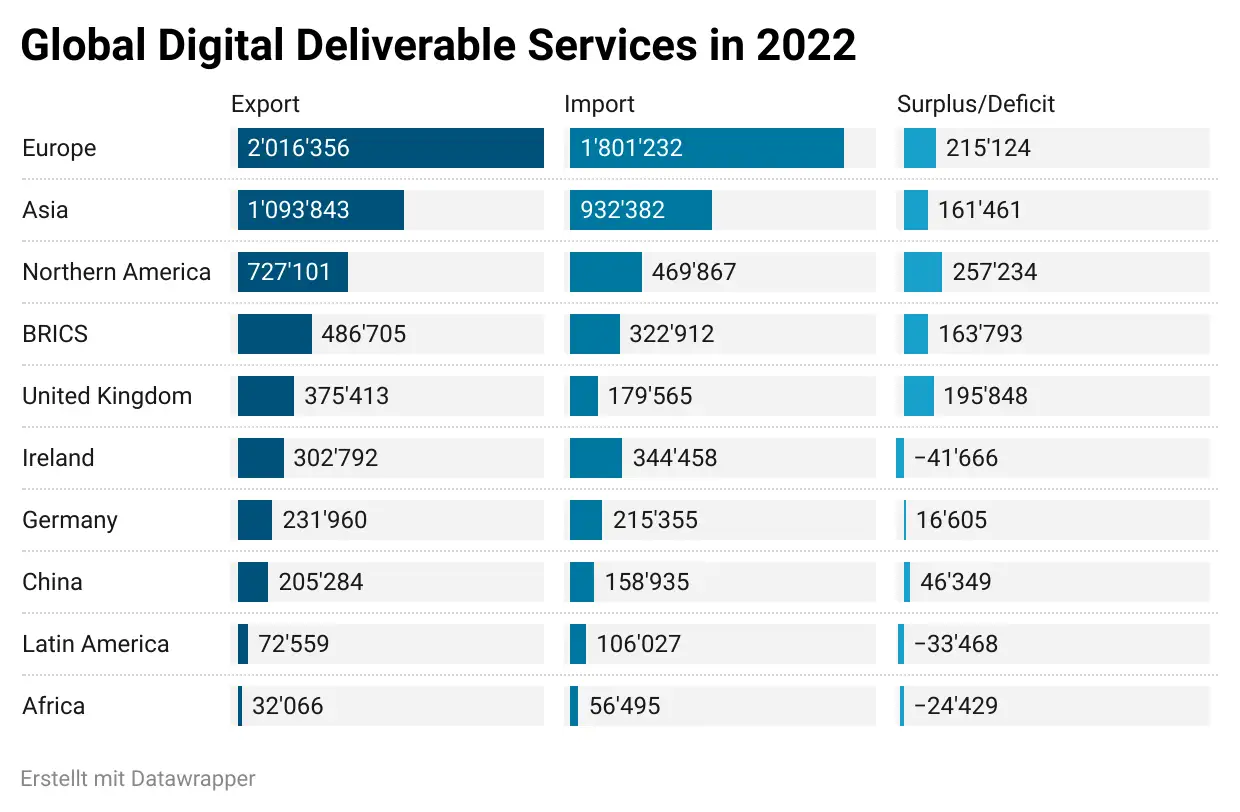

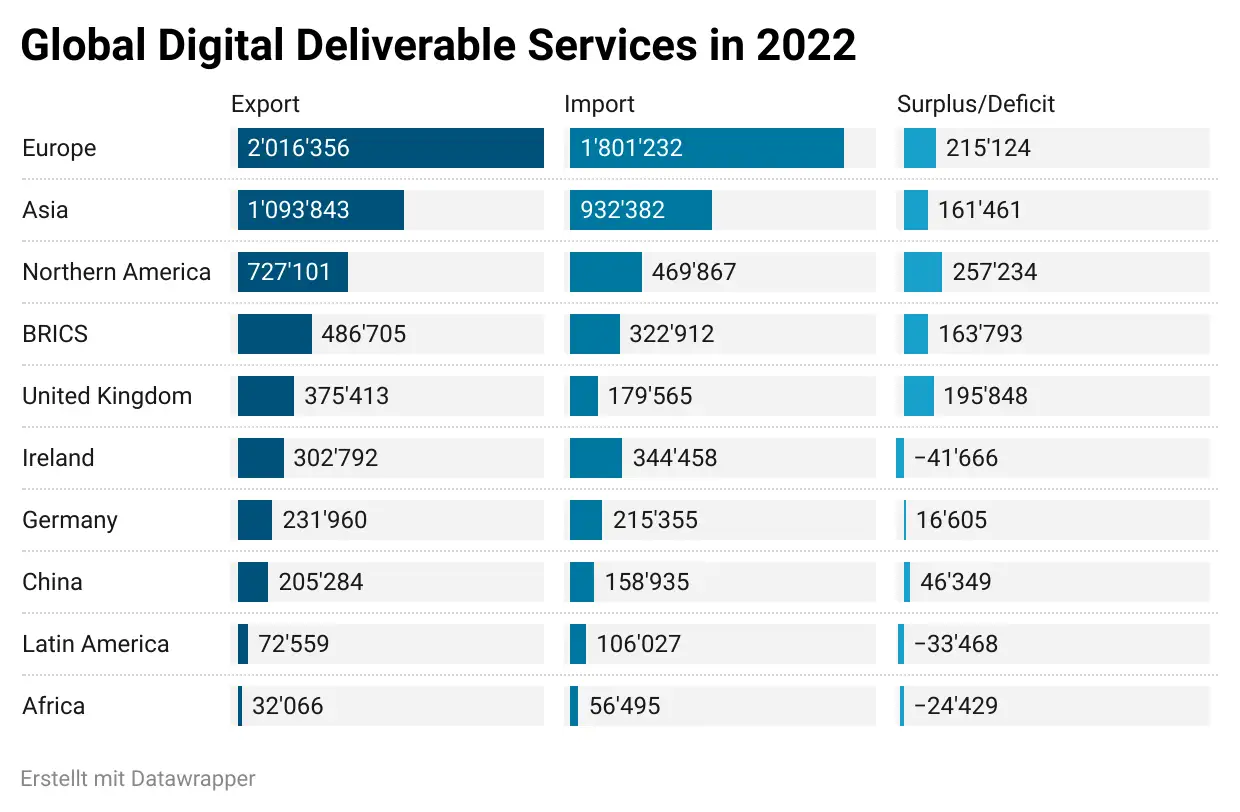

UNCTAD digital deliverable services statistics

An alternative perspective is to examine the data on digital service delivery from UCTAD, as it may provide insight into the overall global situation. According to their publication "Measuring the value of e-commerce", measuring the exchange of paid digital goods and services can be a complex task.

One way to gauge a business's success is by asking about their sales numbers, but I believe the informal online economy (such as creators, social commerce, and cryptocurrency) is much larger than reported. The UNCTAD also includes standard service industries like finance, consulting, and media in their statistics, while small businesses and creators may fall under different categories or may not be included at all (see full list below 1). However, UNCTAD has uncovered some interesting insights through their data. This gives a wider range of potential services to consider when comparing countries.

Here are some noteworthy findings from the data:

- While the USA is typically seen as the forerunner in digital services, Europe (including the UK) actually has a significantly larger export market - more than double that of the USA and Canada combined. While most attention is given to big tech companies, Europe also boasts a substantial digital services industry and maintains an equal trade surplus compared to North America.

- The BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) have experienced significant growth in digital service exports, almost tripling since 2011. However, 90% of these exports are from China and India combined, still lagging behind Europe in this sector.

- Ireland is a “leader” in digital services within the EU, likely due to its high concentration of major tech companies that have chosen Ireland as their European headquarters. This includes data centers and other supplementary services. Based on UNCTAD statistics, Ireland has a trade deficit that is largely caused by fees for utilizing intellectual property. However, I struggle to understand the reasoning behind this.

- The UK is the largest exporter of digital services in Europe, with no surprise that a third of them are financial, insurance, and pension services.

- Statistics for Latin America and Africa reveal their low representation in the global Internet market. This is unfortunate, as the global market should provide more opportunities for accessibility, but as I mentioned previously in my article on the global small package economy, there are still many obstacles that prevent these regions from competing on an equal level. It should also be noted that UNCTAD's statistics only cover the formal digital economy.

Export and import of digitally-deliverable services in 2022

| Region | Export | Import | Surplus/Deficit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | 2.016.356 | 1.801.232 | 215.124 |

| Asia | 1.068.035 | 896.024 | 172.011 |

| Northern America | 727.101 | 469.867 | 257.234 |

| BRICS | 486.705 | 322.912 | 163.793 |

| Latin America | 72.559 | 106.027 | -33.468 |

| Africa | 32.066 | 56.495 | -24.429 |

| China | 205.284 | 158.935 | 46.349 |

| Ireland | 302.792 | 344.458 | -41.666 |

| Germany | 231.960 | 215.355 | 16.605 |

| United Kingdom | 375.413 | 179.565 | 195.848 |

In conclusion, both Stripe and UNCTAD offer intriguing data that highlights the rapid expansion of digital products and services. However, it is important to note that while this growth is significant, it does not paint a complete picture of the diverse digital global economy. The rise of small businesses and the informal economy must also be taken into consideration when examining the impact of the internet. These lesser-known sectors play a crucial role in shaping the digital landscape and should not be overlooked in discussions about its growth and influence. However, there is limited information and statistics available about them.

date: 2024-04-14 15:20:23 layout: post title: "From Tangible to Intangible: The Evolution of Global E-commerce in the Digital Age" image: "2024/digital-deliverable-services.webp" alt_image: "Smart Phone Digital Literacy Plattform" caption: "Chart by Datawrapper and data by UNCTAD on digital deliverable services in 2022." description: "Explore the evolution from physical goods to digital products in e-commerce. Understand how digital trade is reshaping global commerce, its challenges, and the opportunities for small businesses in a digital economy." lang: en categories:

- digital-economy

Ecommerce: The Difference between Physical and Digital Goods

As the digital economy continues to grow, so do non-tangible products. Often, when discussing ecommerce online, the focus is solely on selling physical goods. However, it is important to distinguish between the two domains of selling physical products and digital products or services because they have entirely different business models. Physical products require inventory and storage, as well as relying on certain logistics. Platforms like Shopify have built a whole ecosystem to support small business owners in selling their products, while Etsy offers a platform for selling artisanal products from the comfort of one's own home. Physical products also face geographical challenges when sold internationally; the recent example of Brexit causing complicated customs regulations has significantly impacted many small online retailers' businesses. I have written more about this issue here.

Selling digital products and services has become much easier online. In the past, during the early 2000s, not many people would have been willing to pay for online courses, excel templates, or ebooks because payment systems were not available and these types of digital products were not widely offered. However, over the last decade, there has been a significant shift in this trend as online courses and templates for various services (such as Notion) have emerged as potential sources of revenue.

The Growth in Digital Trade

Products and services like these pique my interest, as they have the potential to be developed and sold globally. However, for those living in developing countries, obtaining a payment gateway that is accepted can be quite challenging. Even Stripe, one of the largest online payment-processing services, is only available in 46 countries.

However, the digital economy is filled with a wide variety of niche products and services that continue to gain traction, although there is limited data available. This mirrors the issue discussed in my recent article on the global freelance economy. A noteworthy perspective can be found in Stripe's report "How Digital Trade is Reshaping the Global Economy" set for release in 2023, which focuses on small and micro businesses but only includes a select group of countries.

- 59% of consumers are open or somewhat open to purchase a digital service from abroad in 2023

- 88% of education businesses sell internationally today, and 70% plan to expand further internationally in the next two years.

- 81% of sole proprietor businesses in our survey now sell to more than one market, heralding the rise of single-person multinationals. Eighteen percent of these sell to more than 11 global markets.

According to Stripe these are the top 10 digital exports categories by cross-border payment in 2022

- Software (fully digital)

- Clothing and accessoires

- Travel and lodging

- Business services (potentially fully digital)

- Merchandise

- Education (potentially fully digital)

- Ticket and events

- Speciality retail

- Digital goods (digital)

- Person services (potentially fully digital)

Half of the categories can be considered completely digital in nature, consisting of various online products and services. These digital trade routes are seeing immense growth between countries according to data from Stripe. For example, there is a new trade route emerging with a growth rate of 89% between France and Germany from 2020 to 2021, and a staggering 150% growth rate between Japan and Taiwan.

UNCTAD digital deliverable services statistics

An alternative perspective is to examine the data on digital service delivery from UCTAD, as it may provide insight into the overall global situation. According to their publication "Measuring the value of e-commerce", measuring the exchange of paid digital goods and services can be a complex task.

One way to gauge a business's success is by asking about their sales numbers, but I believe the informal online economy (such as creators, social commerce, and cryptocurrency) is much larger than reported. The UNCTAD also includes standard service industries like finance, consulting, and media in their statistics, while small businesses and creators may fall under different categories or may not be included at all (see full list below 1). However, UNCTAD has uncovered some interesting insights through their data. This gives a wider range of potential services to consider when comparing countries.

Here are some noteworthy findings from the data:

- While the USA is typically seen as the forerunner in digital services, Europe (including the UK) actually has a significantly larger export market - more than double that of the USA and Canada combined. While most attention is given to big tech companies, Europe also boasts a substantial digital services industry and maintains an equal trade surplus compared to North America.

- The BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) have experienced significant growth in digital service exports, almost tripling since 2011. However, 90% of these exports are from China and India combined, still lagging behind Europe in this sector.

- Ireland is a “leader” in digital services within the EU, likely due to its high concentration of major tech companies that have chosen Ireland as their European headquarters. This includes data centers and other supplementary services. Based on UNCTAD statistics, Ireland has a trade deficit that is largely caused by fees for utilizing intellectual property. However, I struggle to understand the reasoning behind this.

- The UK is the largest exporter of digital services in Europe, with no surprise that a third of them are financial, insurance, and pension services.

- Statistics for Latin America and Africa reveal their low representation in the global Internet market. This is unfortunate, as the global market should provide more opportunities for accessibility, but as I mentioned previously in my article on the global small package economy, there are still many obstacles that prevent these regions from competing on an equal level. It should also be noted that UNCTAD's statistics only cover the formal digital economy.

Export and import of digitally-deliverable services in 2022

| Region | Export | Import | Surplus/Deficit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | 2.016.356 | 1.801.232 | 215.124 |

| Asia | 1.068.035 | 896.024 | 172.011 |

| Northern America | 727.101 | 469.867 | 257.234 |

| BRICS | 486.705 | 322.912 | 163.793 |

| Latin America | 72.559 | 106.027 | -33.468 |

| Africa | 32.066 | 56.495 | -24.429 |

| China | 205.284 | 158.935 | 46.349 |

| Ireland | 302.792 | 344.458 | -41.666 |

| Germany | 231.960 | 215.355 | 16.605 |

| United Kingdom | 375.413 | 179.565 | 195.848 |

In conclusion, both Stripe and UNCTAD offer intriguing data that highlights the rapid expansion of digital products and services. However, it is important to note that while this growth is significant, it does not paint a complete picture of the diverse digital global economy. The rise of small businesses and the informal economy must also be taken into consideration when examining the impact of the internet. These lesser-known sectors play a crucial role in shaping the digital landscape and should not be overlooked in discussions about its growth and influence. However, there is limited information and statistics available about them.

date: 2024-03-13 15:20:23 layout: post title: "E-Commerce's Dual Realities and Their Impact on Small Online Businesses Globally" image: "2024/package-delivery.webp" alt_image: "Small Package delivery" caption: "Photo by Andrew Dallos on Flickr" description: "Explore the contrasting worlds of digital and physical e-commerce, understanding their global trade impacts and challenges for small online businesses. Dive into insights and strategies for navigating these dual realities effectively." lang: en categories:

- digital-economy

E-commerce, likened to a coin with two distinct sides, embodies the dichotomy between digital and physical goods and products. This metaphor illustrates not just the diversity of e-commerce but also the unique challenges and opportunities each side presents.

Digital Products and Services: A Transformational Landscape

The landscape of digital products has undergone a radical transformation since the 2000s. Initially, the concept of purchasing digital services online was met with skepticism. However, the advent of social media and e-commerce ecosystems, such as Shopify, revolutionized this space. These platforms democratized online sales, enabling virtually anyone to market their products from the comfort of their living room, provided they reside in the right country.

This digital boom has seen a surge in the sale of online courses, ebooks, and even Excel templates on platforms traditionally associated with handmade goods, like Etsy. Even seemingly niche products, like sales templates for the information platform Notion, have millions of users.

However, the digital marketplace is not without its challenges. A 2019 UNCTAD study revealed that a majority of developing countries within the WTO import more digitizable goods than they export, highlighting the imbalance in global digital trade.

During their most recent ministerial meeting, the World Trade Union once again extended the Ecommerce moratorium - a longstanding agreement among WTO members to prevent customs duties from being imposed on electronic transmissions. This highlights the difficulties of reaching global consensus in the digital world and regulating the flow of data. As digital products and services continue to grow, governments struggle to collect taxes from this sector. Therefore, many countries are now pursuing the Data Free Flow with Trust (DFFT) concept. In addition, OECD countries are working towards implementing a global digital tax, which is currently being facilitated by the OECD and could potentially be implemented in some countries within the next few years.

Physical Goods: Bridging Local and Global Markets

Informal and formal social commerce have become a global trend, with platforms like Facebook shops, TikTok sellers, and WhatsApp shopping communities gaining widespread popularity. While Western sellers can easily create an online shop and start selling, it is much more challenging for small businesses in other countries to establish an online presence. A study on "Selling Chinese fashion in Mozambique via WhatsApp" showcases the creativity of individuals using these platforms. Due to limited access to specialized e-commerce sites, many small-scale traders in developing regions have turned to WhatsApp to promote their products within their networks. Some have even found success running their businesses from home. Although these platforms have the potential to connect buyers and sellers from rural and urban areas, they struggle to expanded across international borders.

While Chinese companies like Alibaba have the capability to ship even the smallest purchases to customers around the world, this surge in packages has caused significant challenges for customs officials worldwide. In fact, Alibaba has made it their goal to reach international customers in just 72 hours, highlighting the impact of small package trade. Even the Russian postal system has been overwhelmed by this successful approach.

In China, entire villages have been transformed into production hubs for e-commerce businesses. Through government subsidies, these villages focus on a specific product and sell it online - whether it be silver teapots, folding chairs, or bamboo shoots. This has significantly increased the income of these villages. However, having local expertise in digital technology, efficient logistics, and strong digital connectivity are crucial for their success. In addition to these abilities, the main advantage of this village is its strategic placement within the country. The goal is to have all deliveries made within 24 hours, making it a competitive edge over other villages.Thanks to a more efficient logistic system, small businesses in Chinese villages now have the chance to export their products. This is a dream that sellers in other countries can only imagine.

The small package trade

Is there potential for small business owners and social sellers to tap into the global consumer market? In a study by Chris Foster, titled "The Minor Rules Shaping the Development Impacts if Digital Marketplaces," he explores the intricacies of cross-border small package trade for these businesses.

As e-commerce and platform-based trading expand across the globe, one of the major developmental claims is that digital marketplace trading might unleash small firm creativity and profits. Selling online, even reaching lucrative foreign customers, has been a key ambition for many small firms and wider digital development policies.

Foster argues that in the initial phases of e-commerce growth in a nation, the success of digital marketplaces depends heavily on efficient small package logistics. However, there are many obstacles faced by small businesses attempting to broaden their reach to other countries. Foster also notes the adverse effects of a better small-package system in Malaysia, where local companies were overshadowed by Chinese imports, leading to overall economic losses for the country. This situation was reversed for online sellers in the United Kingdom after Brexit, when shipping packages to the European Union became significantly more challenging.

However, challenges can arise at various stages of the customer journey. During my visit to Pakistan, while talking to entrepreneurs in Peshawar, I heard their frustrations with a common issue: the inability to use Western payment systems. These entrepreneurs had quality products and skilled IT teams, but they were hindered by the lack of convenient payment channels for international consumers.

Footnotes

- The following digitally-deliverable services are taken into account: Professional and management consulting services, Architectural, engineering, scientific, and other technical services, Trade-related services, Other business services n.i.e., Audiovisual and related services, Education services, Heritage and recreational services, Health services, Insurance and pension services, Financial services, Charges for the use of intellectual property n.i.e., Telecommunications, computer, and information services, Research and development (R&D) ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4